- Is your scalp flaky, itchy, and red? You might be dealing with seborrheic dermatitis.

- Confused about dandruff vs. seborrheic dermatitis? We clarify the differences.

- Seeking effective treatments? Explore medical, home remedies, and barrier repair solutions.

- Want long-term relief? Learn how to manage symptoms and improve scalp health.

This article is your in-depth guide to understanding and treating seborrheic dermatitis on the scalp. We’ll break down the complexities of this common condition, explore proven treatments, and empower you to make informed decisions for a healthier scalp. If you encounter unfamiliar terms or concepts, please ask in the comments below!

Understanding Seborrheic Dermatitis of the Scalp

Let’s start with the fundamentals of scalp seborrheic dermatitis. Knowing the basics is crucial for making informed treatment choices. If you’re already familiar with the condition, you can skip to the Treatments Section.

How Common is Scalp Seborrheic Dermatitis?

Seborrheic dermatitis affects a significant portion of the population, estimated at 3-5% [13]. This number can rise dramatically, reaching 40-50% in individuals with certain medical conditions like HIV/AIDS.

Scalp and Beyond: Areas Affected

The scalp is the most frequently affected area, where seborrheic dermatitis is often referred to as dandruff. However, “scalp seborrheic dermatitis” can be a more precise term, as the condition can extend beyond the scalp.

If your symptoms are limited to your scalp, consider yourself fortunate. Seborrheic dermatitis can become more persistent and aggressive when it spreads to other areas, including:

- Nasolabial folds

- Hairline

- Ears

- Eyebrows

- Eyelids

- Chin

- Forehead

In rarer instances, symptoms can appear below the neckline, affecting the chest, upper back, and groin.

A key characteristic of these areas is their abundance of sebaceous glands, which secrete sebum (skin oil). Sebum plays a crucial role in the development of seborrheic dermatitis. The scalp is unique due to its high concentration of sebaceous glands and hair cover. While the impact of hair on seborrheic dermatitis isn’t fully understood, it definitely complicates treatment options.

Recognizing the Symptoms

Hallmark symptoms of seborrheic dermatitis include:

- Skin flakes: Varying significantly in size, from fine to large and noticeable.

- Dryness: The scalp may feel tight and dehydrated.

- Inflammation and redness: Affected areas can appear pink or red.

- Irritation and skin sensitivity: The scalp can become easily irritated and reactive.

- Itch: A common and often bothersome symptom.

- Excessive sebum production: While not always present, some experience increased scalp oiliness.

Seborrheic dermatitis is characterized by flare-ups, with symptoms fluctuating in intensity. Sometimes they subside, and other times they erupt and become difficult to manage.

Why Accurate Diagnosis Matters

If you suspect you have seborrheic dermatitis but aren’t certain, getting a confirmed diagnosis is essential. Accurate diagnosis is the cornerstone of effective management. Treating the wrong condition can waste time and money on ineffective treatments.

Unraveling the Causes of Seborrheic Dermatitis

Despite extensive research, the exact cause of seborrheic dermatitis remains unclear. However, the prevailing theory points to a combination of factors. Ongoing advancements in genetic sequencing may offer clearer insights in the future, but for now, the current working theory provides the best explanation.

This theory centers around the interaction of three key elements:

- Malassezia yeasts: A type of fungus naturally found on the skin.

- Sebaceous gland secretions (sebum): Skin oil that provides nourishment for Malassezia.

- Individual susceptibility: Unique factors in each person that influence their reaction to Malassezia and sebum.

These three factors are consistently highlighted in medical literature regarding seborrheic dermatitis.

The Skin Microflora: A Broader Perspective

Emerging research suggests that the overall skin microflora, the complex community of microorganisms on our skin, may have a more significant role than Malassezia alone. We’ll delve into this later.

Malassezia Yeasts: The Prime Suspect

Malassezia yeasts have been the focus of much research. They are considered commensal organisms, meaning they normally live on human skin without causing harm. However, under certain conditions, they can become pathogenic and contribute to conditions like pityriasis versicolor and Malassezia folliculitis [1].

In seborrheic dermatitis, the role of Malassezia is less straightforward. While they don’t appear to transform into their pathogenic hyphae form [2], they are still implicated in the condition’s development.

The link is largely based on the observation that antifungal treatments often lead to rapid symptom improvement. This is thought to be due to the reduction of Malassezia activity on the skin surface. This connection has led decades of research to conclude that these yeasts play a critical role [4].

Currently, the primary understanding is that an overgrowth of Malassezia yeasts is central to seborrheic dermatitis. Reducing Malassezia activity typically leads to symptom relief.

Malassezia Species: Could Specific Types Matter?

Studies comparing the skin microflora of individuals with and without seborrheic dermatitis have revealed differences in the proportions of specific Malassezia species [3]. This suggests that certain species might be more involved in the condition.

Oleic Acid and Scalp Irritation

Malassezia yeasts rely on lipids (fats and oils) for their growth, and sebum, rich in lipids, provides an ideal environment and nutrient source. As Malassezia breaks down sebum, it produces byproducts, including enzymes, free fatty acids, and phospholipases. One notable byproduct is oleic acid in its free fatty acid form.

Intriguingly, even when Malassezia yeasts are reduced with antifungal pretreatment, applying oleic acid directly to the skin of susceptible individuals can trigger irritation, disrupt the skin barrier, and cause symptoms identical to seborrheic dermatitis and dandruff [4, 5, 6].

This suggests that the symptoms of seborrheic dermatitis might be caused by oleic free fatty acids, a byproduct of Malassezia activity, rather than the yeasts themselves. In this scenario, Malassezia’s role is contributory, producing oleic acid on the skin’s surface.

The Crucial Role of a Healthy Skin Barrier

Your skin acts as a vital protective barrier against the external environment. This barrier, the outermost layer of your skin, employs various mechanisms to defend against foreign invaders and antigens.

In individuals with seborrheic dermatitis, this skin barrier is often compromised [7]. This allows external irritants to penetrate deeper skin layers, leading to increased irritation, inflammation, and also contributing to moisture loss and dryness.

While oleic acid can directly damage the skin barrier, individual differences in barrier function likely determine who develops seborrheic dermatitis. A robust skin barrier should neutralize topical irritants effectively, preventing the skin’s immune system from overreacting.

Recent Insights: The Microbial World

Beyond Fungi: The Bacterial Connection

While research has traditionally focused on the fungal aspect (Malassezia), recent investigations highlight the potential significance of bacteria in seborrheic dermatitis [8, 9].

Key findings from these studies include:

- Bacteria and Dandruff Severity: The types of bacteria on the skin show a stronger correlation with dandruff severity than fungi [10].

- Combined Microbial Impact: Both bacteria and fungi are linked to dandruff and seborrheic dermatitis, but skin symptoms appear more closely related to the bacterial flora [11].

- Microbial Shift: Changes in the entire skin microflora are more strongly associated with seborrheic dermatitis than just Malassezia populations [12].

These findings suggest that future research may uncover new treatment approaches and long-term management strategies targeting the broader skin microflora.

Scalp Seborrheic Dermatitis: Unique Characteristics

Seborrheic dermatitis on the scalp has distinct features that influence its development and treatment. Understanding these nuances can provide valuable insights and improve your chances of successful management.

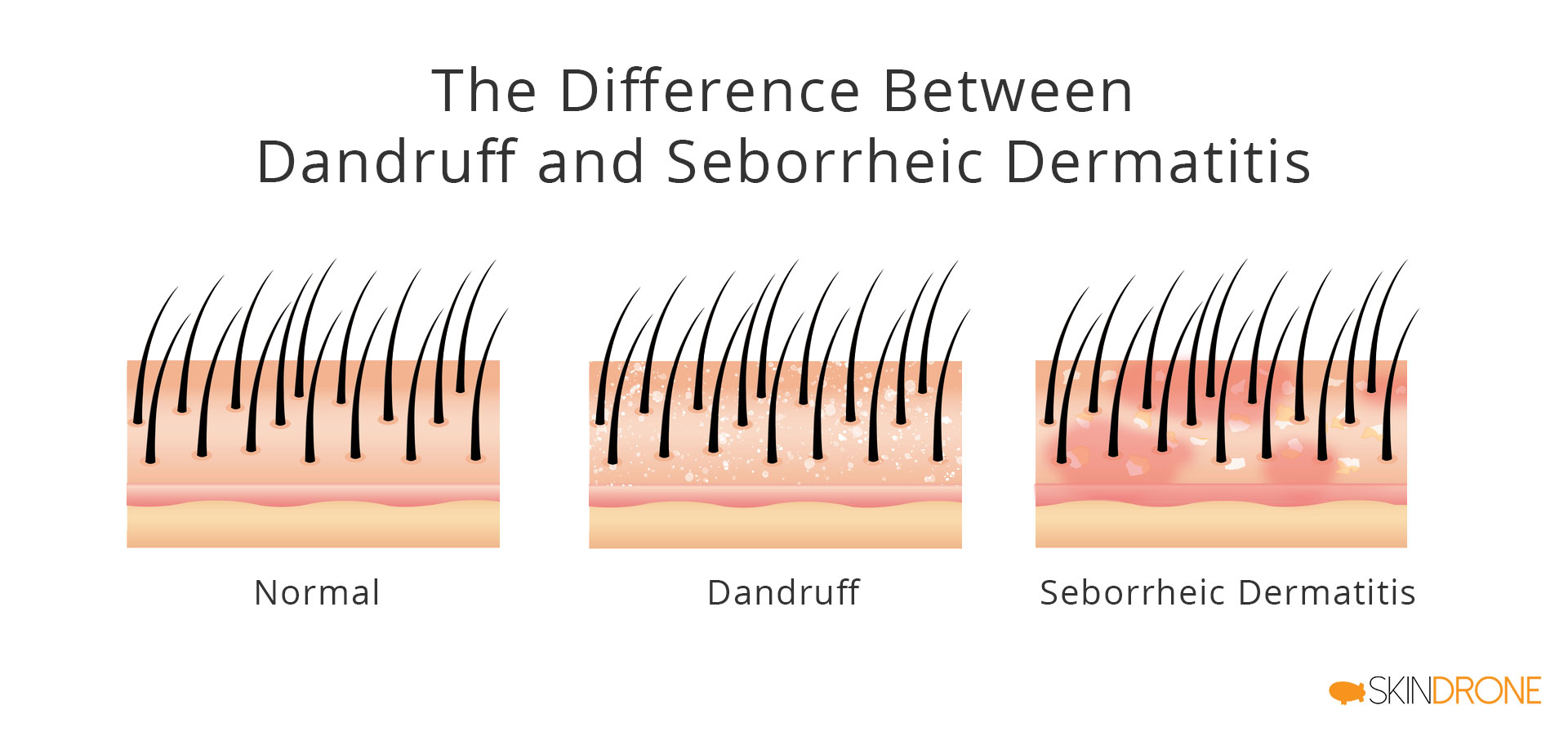

Dandruff vs. Seborrheic Dermatitis: Are They Different?

The terms “seborrheic dermatitis” and “dandruff” are often used interchangeably when referring to the scalp. Most medical literature considers them to be the same condition, with the main distinction being that dandruff is limited to the scalp, while seborrheic dermatitis can occur elsewhere [13].

However, some researchers propose a further differentiation:

- Dandruff: Milder symptoms, limited in severity.

- Seborrheic Dermatitis: A more aggressive form of dandruff.

While not universally accepted, this distinction may be helpful. Separating them could improve our understanding of how dandruff progresses to more severe seborrheic dermatitis and spreads beyond the scalp. It’s possible that dandruff is an early stage of seborrheic dermatitis, acting as an initial warning sign.

Clinical Distinctions

Some experts even describe specific clinical differences [14]:

Dandruff:

- Characterized by scales and subclinical inflammation (inflammation that’s very difficult to detect), restricted to the scalp. More specifically, it shows “scattered presence of lymphoid cells and squirting capillaries in the papillary dermis, hints of spongiosis and focal parakeratosis.”

Seborrheic Dermatitis:

- Characterized by scales, significant inflammation, often extending beyond the scalp. More specifically, it presents as “spongiotic dermatitis in which mounds of parakeratosis and scale crusts form at lips of infundibular ostia.”

While the more detailed descriptions can be complex, the key takeaway is that scalp seborrheic dermatitis can be viewed as a more intense form of dandruff with inflammation as a primary feature.

Hair’s Impact on Seborrheic Dermatitis

Hair follicles have been suggested as potential reservoirs for drug delivery, potentially enhancing the effectiveness of topical treatments [15]. This would imply that treatments might work better in hair-bearing areas.

However, those with seborrheic dermatitis know that hair often makes the condition harder to manage. A 1993 review even suggested that shaving affected areas can significantly improve or even resolve symptoms [16].

Unfortunately, shaving the scalp isn’t a practical solution for most. We must acknowledge the challenges hair presents and adjust treatment strategies accordingly.

Hair Products and Irritation

Some researchers have proposed that scalp seborrheic dermatitis might arise without microbial involvement, simply as a reaction to irritating hair care products or environmental substances [17].

For some, switching hair products might be enough to trigger and maintain remission. If you explore this route, compare product ingredient lists carefully, focusing on the first 3-5 ingredients, as these are present in the highest concentrations. However, be aware that many products share similar base ingredients.

The Role of Heat

Heat might also play a role in seborrheic dermatitis. Thermal imaging studies indicate that areas commonly affected by seborrheic dermatitis, particularly on the face, tend to have higher skin temperatures:

- [Relation Between Skin Temperature and Location of Facial Lesions in Seborrheic Dermatitis][1]

One theory suggests that increased skin temperature could lead to increased Malassezia activity and, consequently, more oleic free fatty acid production. Alternatively, it’s possible that the high density of sebaceous glands in these areas leads to increased blood flow and higher skin temperature, making temperature a secondary factor.

Hair Loss and Seborrheic Dermatitis

Hair loss isn’t directly a symptom of scalp seborrheic dermatitis or dandruff. However, if these conditions become severe and are left unchecked, hair loss can become a concern.

This is often due to:

- Physical damage: Scratching and picking at the scalp.

- Hair follicle blockage: Flakes and scales can clog hair follicles.

- Inflammation: Chronic inflammation can disrupt hair growth cycles.

These factors can weaken hair, making it thinner and more prone to breakage [], leading to noticeable hair loss.

One study showed that individuals with dandruff lost significantly more hair (100-300 hairs daily) compared to those without (50-100 hairs daily) [pubb id=”18489295″]. This suggests that seborrheic dermatitis can lead to 2-6 times more hair shedding than normal.

Fortunately, many seborrheic dermatitis treatments can reduce hair loss and promote healthier hair growth. Addressing the scalp condition often resolves associated hair loss issues. This is discussed further in this article: Reversing Seborrheic Dermatitis and Hair Loss.

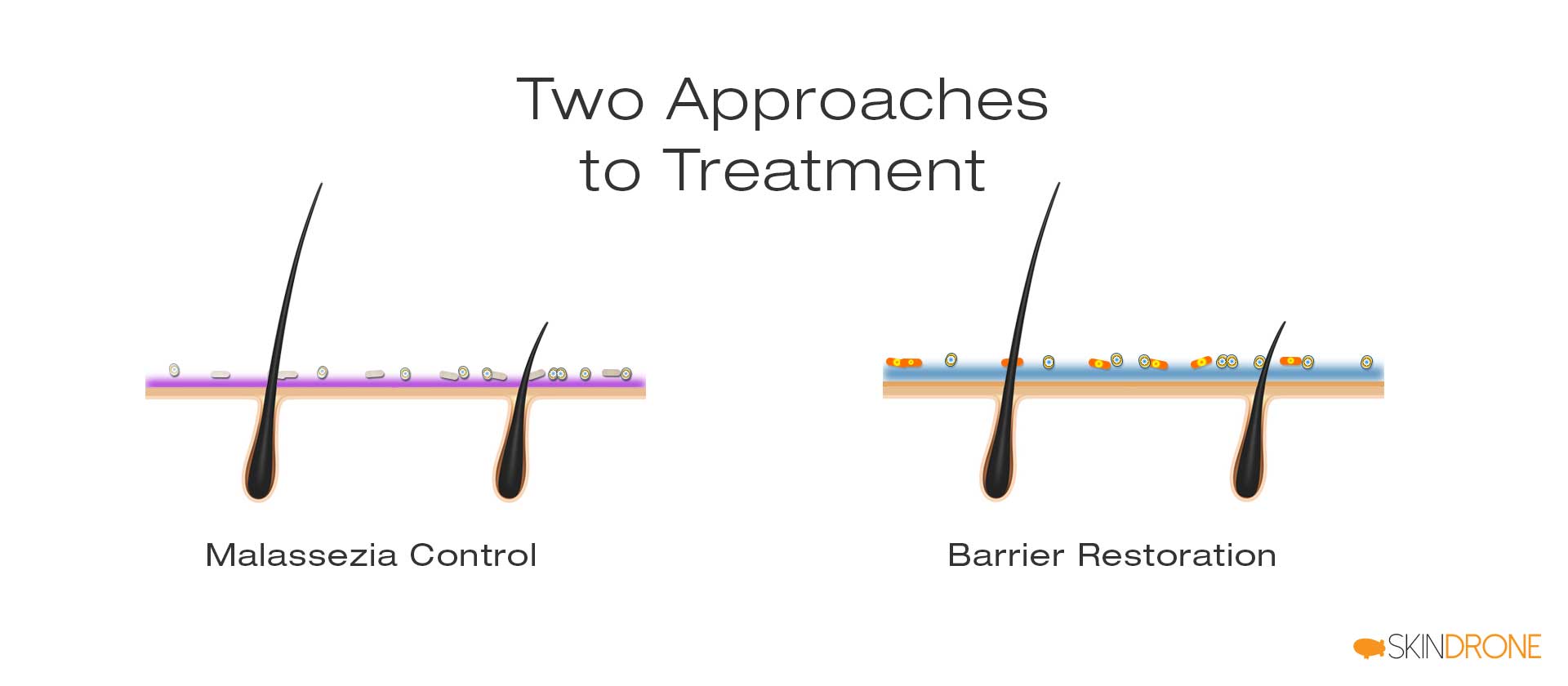

Treatment Strategies: A Two-Pronged Approach

Given the multifaceted nature of seborrheic dermatitis, effective treatment should address two key aspects:

- Reducing Malassezia and oleic acid levels.

- Improving and restoring the skin barrier function.

While targeting just one of these can provide some relief, a combined approach is more likely to achieve long-term success.

1. Irritant Reduction: Antifungal Treatments

Based on the theory that Malassezia byproducts trigger symptoms, antifungal agents are a primary treatment for scalp seborrheic dermatitis. They reduce Malassezia activity and often provide rapid relief.

The action pathway is:

Antifungal → Reduced Malassezia → Reduced Oleic Acid → Symptom Relief

However, some evidence suggests that antifungals might work differently than simply reducing Malassezia. While they effectively suppress Malassezia in lab settings [19, 20, 21], their impact on skin surface Malassezia counts in real-world use is often minimal []. It’s possible they provide relief by influencing fungal/host gene expression or affecting the inflammatory process.

2. Skin Barrier Restoration

As discussed earlier, compromised barrier function is a significant factor in seborrheic dermatitis. While systemic approaches like diet and stress management can help, specially formulated topical products can also improve barrier function and prevent further disruption.

Strengthening the skin barrier can reduce the irritant effects of Malassezia and oleic acid, leading to gradual symptom improvement.

The action pathway is:

Barrier Repair → Reduced Sensitivity → Lack of Symptoms

This approach aims for longer-term relief by enhancing the skin’s natural defenses rather than just eliminating Malassezia, which is a normal skin inhabitant. While barrier repair strategies are still evolving, they hold significant promise for the future.

Review of Popular Treatments

Now, let’s explore specific treatments, keeping in mind the two key approaches we just discussed.

No One-Size-Fits-All Treatment

Everyone’s skin is unique, so no single treatment works perfectly for everyone. Trying different options is often necessary to find what works best for you.

Antifungal Shampoos: Ingredient-Based Guide

Antifungal shampoos are a well-established starting point for scalp seborrheic dermatitis. Different antifungal agents work in different ways and have varying effectiveness against different Malassezia species. If one antifungal doesn’t work, another might.

Also, individuals can be sensitive to specific ingredients in hair products. Trying different formulations with the same antifungal active ingredient but different overall compositions can be beneficial.

Similar Formulas Within Antifungal Groups

Shampoos with the same active antifungal often have very similar overall formulas. Pay attention to ingredient lists and compare them carefully.

Zinc Pyrithione Shampoos

Zinc pyrithione is the active ingredient in Head & Shoulders, the world’s most popular dandruff shampoo. It has a strong safety record and few reported side effects [22].

Zinc pyrithione is known to suppress a broad range of Malassezia species. Some theories suggest its benefits might also stem from its toxicity to epidermal cells, effectively dampening the immune response [23].

A study on a 1% zinc pyrithione shampoo showed complete clearance in 28.8%, marked improvement in 53.1%, and moderate improvement in 11.9% of participants with scalp seborrheic dermatitis over 4 weeks [24]. 5% saw no relief, and 1.3% worsened.

Zinc pyrithione products are widely available, including shampoos, conditioners, creams, ointments, and soaps.

Their high success rate, accessibility, and affordability make zinc pyrithione shampoos and conditioners a common first choice.

Common Zinc Pyrithione Shampoos:

- Head and Shoulders – Classic Clean (and most other H&S varieties)

- Neutrogena T/Gel (1% zinc pyrithione)

- Suave Men 2-in-1 Anti Dandruff Shampoo & Conditioner

- Dove Men+Care Anti Dandruff 2 in 1 Shampoo and Conditioner

- Dove Dermacare Anti Dandruff Scalp Shampoo

- Equate Everyday Clean Dandruff Shampoo

- Mountain Falls 2-in-1 Dandruff Shampoo (Amazon brand)

Alternative Zinc Pyrithione Options:

- Vanicream Free & Clear Medicated Anti-Dandruff Shampoo

- DHS Zinc Shampoo

- Mizani Scalp Care Shampoo & Conditioner

Author's Experience

In my experience, zinc pyrithione shampoo provided quick scalp seborrheic dermatitis relief. However, continued use made my scalp sensitive and thinned my hair. When facial seborrheic dermatitis appeared, I needed to explore other treatments.

Ketoconazole Shampoos

Ketoconazole is another popular antifungal, belonging to the azole family. It’s widely prescribed for both seborrheic dermatitis and dandruff globally.

Ketoconazole appears to be more effective than zinc pyrithione [24]. In the same comparison study, a 2% ketoconazole shampoo resulted in complete clearance in 39.6%, marked improvement in 46.2%, and moderate improvement in 10.7% of participants.

Like zinc pyrithione, ketoconazole is thought to work by suppressing Malassezia, although its exact mechanism may involve regulating fungal/host gene expression or influencing inflammation.

The most common ketoconazole product is Nizoral Anti-Dandruff Shampoo.

- Nizoral Anti-Dandruff Shampoo

Other forms like creams and conditioners exist, but are less common and often require a prescription.

Author's Experience

My experience with Nizoral was brief. After one wash, my hair felt stripped and my scalp felt tight. It wasn’t a product I wanted to continue using.

Selenium Sulfide Shampoos

Selenium sulfide is an antifungal agent similar to sulfur. It’s a popular seborrheic dermatitis treatment despite concerns about selenium toxicity.

While less potent than ketoconazole in lab tests [25], it shows similar real-world effectiveness for symptom relief [26]. However, it has a higher chance of side effects [29].

Selsun Blue is the most well-known selenium sulfide shampoo:

- Selsun Blue Medicated Dandruff Shampoo 1% Selenium Sulfide

Head & Shoulders and Amazon also offer alternatives:

- Head and Shoulders Clinical Strength Anti-Dandruff

- Mountain Falls Advanced Solution Dandruff Shampoo – Selenium Sulfide (Amazon brand)

Higher concentrations (2.5% selenium sulfide) are available in lotion/gel form, potentially increasing side effect risks.

Author's Experience

I have no personal experience with selenium sulfide. It became relevant to me after I shifted focus from antifungals to barrier repair.

Coal Tar Shampoos

Tars, including coal tar, pine tar, and sulfonated shale oil, are used for various skin conditions []. Coal tar is the most popular.

Coal tar is a complex byproduct of coal, containing thousands of compounds [29].

Like other antifungals, it’s believed to work by suppressing Malassezia [30]. It also has keratolytic properties (softening skin) [31] and anti-inflammatory effects [32].

Coal tar effectively relieves seborrheic dermatitis symptoms and is a good alternative to other antifungals [33]. It has a long history of safe use [34].

Neutrogena T/Gel is a popular coal tar shampoo:

- Neutrogena T/Gel Therapeutic Shampoo Original Formula – 4.0% Solubilized Coal Tar Extract (0.5% Coal Tar)

Other coal tar options are available online or in specialty stores:

- MG217 Psoriasis Medicated Conditioning Shampoo – 3% Coal Tar

- ArtNaturals Dandruff Shampoo – 3% Coal Tar

- Mountain Falls Therapeutic Dandruff Shampoo – 2.5% Coal Tar (Amazon brand)

- Walgreens T+Plus Tar Gel Dandruff Shampoo – 4.0% Solubilized Coal Tar Extract (1% Coal Tar)

Coal tar’s strong odor and dark color limit its wider use.

Author's Experience

Coal tar, specifically Neutrogena T/Gel, worked well for my scalp and facial seborrheic dermatitis. However, with time, my facial skin became more sensitive and less vibrant.

Tea Tree Oil Shampoos

Tea tree oil, an essential oil from the Australian tea tree, is effective against fungi, bacteria, and mites [35].

It can suppress Malassezia in the lab [] and at concentrations of 5% or more, may be comparable to azole antifungals.

While research is less extensive than for other antifungals, a study of 126 people showed that 5% tea tree oil shampoo provided similar symptom relief to ketoconazole and terbinafine [37].

Its broad action and natural origin have increased its popularity in skin and hair care.

Paul Mitchell Tea Tree Special Shampoo is a well-known brand:

- Paul Mitchell Tea Tree Special Shampoo

Other widely available brands include:

- Avalon Organics Scalp Treatment Tea Tree Shampoo

- Thursday Plantation Tea Tree Shampoo

- OGX Hydrating TeaTree Mint Shampoo

- JASON Normalizing Tea Tree Treatment Shampoo

- Trader Joe’s Tea Tree Tingle Shampoo

- Maple Holistics Pure Tea Tree Oil Shampoo

[imdy id=”5291″]

Pure tea tree oil can also be diluted and customized.

Author's Experience

My experience with tea tree oil was mixed. Pre-made formulas didn’t work for me, and despite trying various dilutions of pure tea tree oil, I didn’t get significant relief. However, its natural appeal and potential benefits were tempting.

Other Antifungal Options

Many other antifungals are effective against Malassezia. Here are a few additional options to consider:

Piroctone Olamine

Piroctone olamine is another antifungal agent often found in dandruff shampoos, known for its effectiveness against Malassezia. It’s often considered a gentler alternative to some of the harsher antifungals.

Nystatin

Nystatin, originally called fungicidin, was the first successful antifungal agent [], discovered by Rachel Fuller Brown and Elizabeth Lee Hazen [39].

Despite its long history and broad antifungal activity, nystatin isn’t widely used for seborrheic dermatitis, possibly due to Malassezia resistance [] or lower potency compared to azoles [40].

However, nystatin has been shown to be effective [], and some individuals report success when other antifungals fail (see Nystatin A Potential Seborrheic Dermatitis Treatment).

Topical nystatin is mainly available in creams/ointments, making scalp application difficult. But if other treatments haven’t worked, it might be worth considering, especially for non-scalp areas.

Salicylic Acid Shampoos

Salicylic acid, from willow bark, has some antifungal properties [42], but isn’t a recognized antifungal against Malassezia.

Yet, it’s an accepted anti-dandruff treatment and can reduce seborrheic dermatitis symptoms [43]. It’s not typically a standalone solution, often used with antifungals to improve results [44, 45].

Salicylic acid’s main action is keratolytic, softening the skin’s top layer for better flake removal and sebum flow.

Salicylic Acid Shampoos (3% unless noted):

- Neutrogena T/Sal Therapeutic Shampoo

- Dermarest Psoriasis Medicated Shampoo Plus Conditioner

- Avalon Organics Anti-Dandruff Itch & Flake Shampoo – 2% Salicylic Acid

- MG217 Psoriasis Shampoo and Conditioner

- Denorex Extra Strength Dandruff Shampoo and Conditioner

- DHS SAL Shampoo

Combination Shampoo:

- JASON Dandruff Relief Treatment Shampoo (Sulfur & Salicylic Acid)

This combination shampoo aims for enhanced effectiveness, but Amazon reviews are mixed.

Author's Experience

Salicylic acid shampoos like Neutrogena T/Sal are rarely enough for persistent seborrheic dermatitis. However, for mild or occasional flare-ups, they can provide relief.

Home Remedies

With antibiotic resistance on the rise, many seek natural treatment alternatives. For seborrheic dermatitis, some individuals don’t respond to conventional treatments or prefer natural options. Natural approaches have gained popularity and shown promise.

Apple Cider Vinegar (ACV)

Apple cider vinegar rinses are a popular home remedy for scalp seborrheic dermatitis. It’s perhaps the most widely known natural treatment.

Surprisingly, medical literature is limited. A few papers mention a 50/50 water-vinegar solution being effective for dogs [46], but research in humans is scarce.

Theoretically, ACV’s low pH might inhibit some Malassezia species []. If so, any vinegar might work, making the focus on apple cider vinegar less specific.

Popular ACV Choice:

- Braggs Apple Cider Vinegar

Braggs popularized ACV with their “Apple Cider Vinegar Miracle Health System” book.

Alternatives exist, including local producers. Any vinegar might suffice if pH is the key factor.

Author's Experience

My experience with apple cider vinegar was ultimately disappointing. It slightly improved flaking, but results were inconsistent and it irritated my skin.

Further Reading

More on apple cider vinegar for seborrheic dermatitis: Seborrheic Dermatitis and the Potential Use of Apple Cider Vinegar.

Raw Honey

Honey has a long history of use for skin ailments and is common in modern skincare [].

Honey’s skincare benefits include [49]:

- Faster wound healing

- Infection prevention

- Wrinkle reduction

- Skin pH regulation

Researchers have explored its potential for seborrheic dermatitis.

Raw honey, minimally filtered, retains natural waxes. A frequently cited study used a 50/50 raw honey-water mix with significant improvements for most participants [50]. Maintenance use after symptom clearance greatly improved remission times. Online reports support these findings.

Raw vs. Filtered Honey: Is Raw Honey Better?

It’s unclear. Honey quality and pollinating plants might be more important due to antibacterial properties []. The anti-inflammatory wax content might also contribute [52].

The challenges are inconsistent honey quality and the effort required for each treatment (hours-long application, multiple times weekly), especially for scalp treatment due to hair making application difficult.

Raw honey is widely available in supermarkets and farmers markets. Local beekeepers can provide the freshest honey. Effectiveness can vary due to honey’s natural variability, making specific recommendations difficult.

Author's Experience

Honey was the best home remedy I tried for facial seborrheic dermatitis. However, scalp application was too difficult, so I have no experience with it for scalp use.

Further Reading

More on raw honey: Treating Seborrheic Dermatitis with Raw Honey and eBook section.

Dead Sea Salt

Dead Sea salt, rich in magnesium, is reported to help with various skin issues.

Its benefits are attributed to its ability to [53]:

- Improve barrier function

- Reduce inflammation

- Enhance hydration

These factors are relevant to many skin conditions.

For seborrheic dermatitis specifically, evidence is limited beyond anecdotal reports. However, for psoriasis, a similar condition, Dead Sea salt shows promise [54, 55]. Climatotherapy at the Dead Sea (combining low altitude UV and magnesium-rich water) shows notable improvements [56, 57].

If anecdotal reports are reliable and psoriasis benefits translate to seborrheic dermatitis, Dead Sea salt might be worth trying. It’s inexpensive and easy to use.

Dead Sea salt is available in many supermarkets and online.

Author's Experience

Dead Sea salt worked rapidly and easily for my facial seborrheic dermatitis. However, remission was short-lived, and symptoms quickly returned.

Antifungal Conditioners

While antifungal shampoos are the primary treatment, using a regular shampoo with an antifungal conditioner might be beneficial.

Antifungal shampoos can be irritating due to surfactants (cleansing agents). Switching to a gentler shampoo with an antifungal conditioner could reduce irritation. Conditioners are designed for better penetration and longer-lasting effects, potentially enhancing antifungal action even at lower concentrations.

Popular Zinc Pyrithione Conditioners (Head & Shoulders):

- [Head & Shoulders Instant Cooling Relief Conditioner][2]

- [Head & Shoulders Repair and Protect Conditioner][3]

Other Antifungal Conditioner Options:

- Dr Marder’s A-D Psoriasis & Zinc Pyrithione Conditioner

- Mane’n Tail Pyrithione Zinc Anti-Dandruff Conditioner

- Mizani Scalp Care Conditioner

Co-washing: Consider co-washing, using only conditioner to cleanse hair, eliminating shampoo altogether. Head & Shoulders offers a zinc pyrithione co-wash:

- [Head & Shoulders Moisture Care Co-Wash][4]

While research comparing co-wash conditioners to regular antifungal shampoos is lacking, co-washing might be gentler and reduce barrier disruption, potentially proving superior for seborrheic dermatitis.

Scalp Barrier Repair Solutions

Barrier dysfunction is key in seborrheic dermatitis. Improving barrier function can reduce irritant sensitivity and inflammation.

Instead of eliminating irritants, barrier repair focuses on strengthening skin defenses.

Research on barrier repair for scalp seborrheic dermatitis is limited. One study using a glycerin-based moisturizing scalp gel showed significant improvement in dandruff and symptom severity [58].

Personal experience suggests barrier repair is crucial and potentially more effective than antifungals alone.

For general seborrheic dermatitis, eczema barrier repair creams/ointments can help. For the scalp, finding gentle shampoos designed for sensitive skin is key. These minimize irritation from harsh surfactants and allow the barrier to stabilize, leading to gradual symptom relief.

Gentle Shampoo Options:

- Free & Clear Shampoo for Sensitive Skin

- Puracy Natural Shampoo

- Maple Holistics Hydrate Moisturizing Shampoo

- Nurture My Body All-Natural Everyday Shampoo

- Jason Fragrance-Free Shampoo

- Earth Science Fragrance-Free Shampoo

- Aveeno Pure Renewal Gentle Shampoo

Author's Experience

For two years, Andalou Moisture Rich shampoo provided significant relief, better than antifungals, and made my scalp feel healthier. Unfortunately, a formula change led to symptom recurrence.

Additional Tips for Treatment Success

Regardless of your treatment approach, these factors can improve outcomes:

Extended Application Time

Leaving shampoo on longer can improve effectiveness [59]. Piroctone olamine benefits more from longer exposure than ketoconazole, but even ketoconazole shows some improvement.

However, prolonged surfactant exposure can disrupt the skin barrier [60]. Longer-term studies are needed to fully assess the impact of extended exposure times.

Cooler Water Temperatures

Lower water temperatures during washing can reduce irritation []. Surfactants can be harsh, and minimizing irritation at each wash is helpful. Consider washing hair with cool or cold water.

Author’s Perspective

Seborrheic dermatitis profoundly impacted my life when it spread beyond my scalp to my face. It affected my social life and caused considerable distress.

After years of experimentation, I found solutions and achieved remission. My interest in the root causes remains.

My understanding continues to evolve, but I believe systemic factors are key:

- Metabolic issues (especially fat metabolism)

- Lifestyle (sunlight, location, stress)

- Diet

- Hormones

- Disease states

These factors influence immune stability, systemic inflammation, microbiota, and lipid oxidation, leading to an unstable skin microflora, impaired barrier function, and over-reactivity to irritants.

Topical treatments manage symptoms, but addressing underlying issues is crucial for long-term remission and overall health. This guide focuses on topical treatments. Underlying issues are discussed further here: Seborrheic Dermatitis – The Owner’s Manual.

Summary: Key Takeaways

1. Seborrheic dermatitis is a common, but not fully understood, skin condition affecting sebum-rich areas like the scalp and face.

2. Dandruff and seborrheic dermatitis are often used interchangeably, with seborrheic dermatitis potentially being a more severe form of dandruff.

3. The condition likely results from interactions between Malassezia yeasts, sebum, and individual susceptibility.

4. Hair can complicate scalp seborrheic dermatitis management, and hair loss can be an indirect consequence.

5. Antifungal agents (zinc pyrithione, ketoconazole, selenium sulfide, coal tar, tea tree oil) are the most common treatments.

6. Scalp treatment primarily uses antifungal shampoos and conditioners.

7. Apple cider vinegar, raw honey, and Dead Sea salt are popular home remedies.

8. Improving barrier function through gentle hair washing may be beneficial.

We are all navigating this together. Share your experiences or questions in the comments below.

No Comments

Be the first to start a conversation