- Myth vs. Fact: Separate common misconceptions about oils and seborrheic dermatitis from evidence-based truths.

- Malassezia & Oils: Understand the crucial link between malassezia yeast, oleic acid, and seborrheic dermatitis symptoms.

- Lipid Layer Importance: Learn why stripping away all oils can actually worsen seborrheic dermatitis.

- Practical Strategies: Discover sensible approaches beyond oil elimination, focusing on skin pH, sebum quality, and gentle skincare.

Many people affected by seborrheic dermatitis are wary of using oils in their skincare routine. You’ve probably heard that oils are a definite “no-no” if you’re prone to this condition. But is this advice based on solid evidence, or is it just another skincare myth?

This article dives into the research to uncover the real relationship between oils and seborrheic dermatitis. By the end, you’ll have a clearer understanding, enabling you to make informed decisions to manage your symptoms effectively.

Understanding Seborrheic Dermatitis and Malassezia

The most widely accepted explanation for seborrheic dermatitis involves malassezia, a type of yeast naturally found on everyone’s skin. Numerous studies over the past decade have explored this connection, which we’ve also touched upon in our section on the underlying causes of seborrheic dermatitis.

For a quick recap, here’s the essential point:

In seborrheic dermatitis, malassezia yeast breaks down sebum and deposits oleic acid onto the skin. This oleic acid is the key culprit behind the skin irritation and symptoms associated with seborrheic dermatitis.

Interestingly, oleic acid is also the main fatty acid in olive oil. However, in olive oil, it’s in a triglyceride form, which isn’t considered irritating. It’s when oleic acid is in its free fatty acid form (like in spoiled olive oil) that it can directly irritate the skin and increase sensitivity [1, 2].

What Does Malassezia Need to Grow?

To understand how oils might affect seborrheic dermatitis, it’s helpful to know what malassezia needs to thrive.

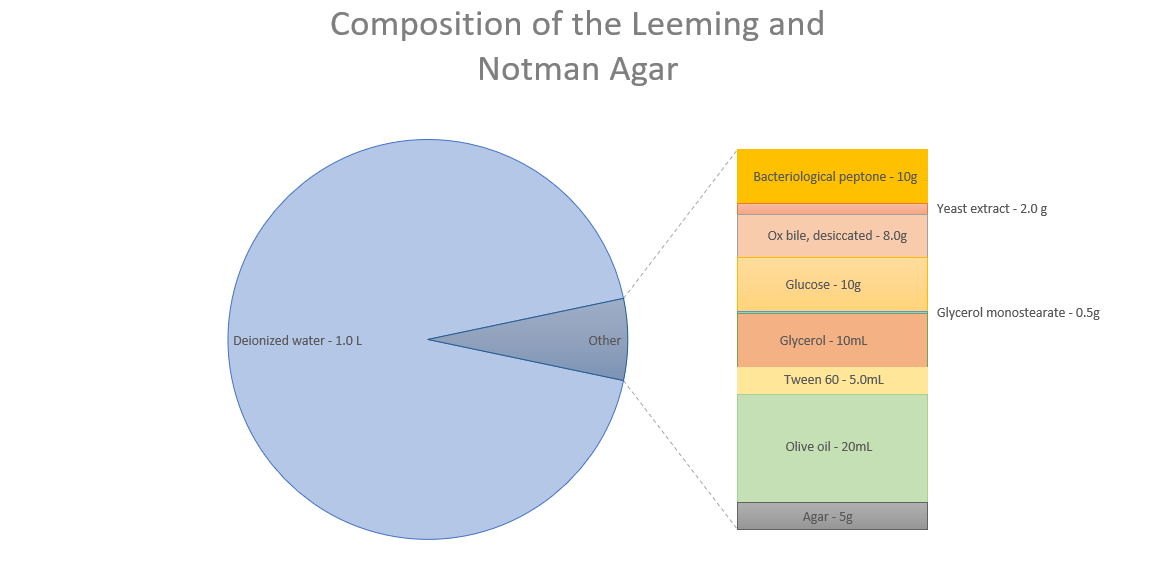

In laboratory settings, researchers use a specific mixture to encourage malassezia growth [3]:

Bacteriological peptone – 10g, glucose – 10g, yeast extract – 2.0 g, ox bile, desiccated – 8.0g, glycerol – 10ml, glycerol monostearate – 0.5g, tween 60 – 5.0ml, olive oil – 20ml, agar – 5g, deionized water – 1.0l

Data source: Leeming & Notman agar Modified MLNA media – ATCC

As you can see, oil is just one component of malassezia’s optimal growth environment. It also requires carbohydrates, electrolytes, vitamins, and trace elements. However, this lab setup aims for optimal growth, and malassezia might survive with far less.

Further research reveals that malassezia furfur, a specific type of malassezia yeast, can grow with just two things: an amino nitrogen source and a lipid source [4]. Put simply, malassezia can grow with almost any protein source (except cysteine) and oils containing more than 12 carbon atoms.

The Misconception: Eliminating Oil to Control Malassezia

Because of these two points:

- The strong link between malassezia and seborrheic dermatitis.

- Malassezia’s need for oils/lipids to grow.

Many online sources and media outlets quickly conclude that oils are a major trigger for seborrheic dermatitis. It’s easy to see how this idea becomes widespread.

But is it really that simple? Is oil the enemy? Can we realistically eliminate all oils from our skin?

Our skin naturally produces oils for protection. Completely removing all oil contact would be extremely difficult and potentially harmful. Let’s delve deeper to clarify things.

Why Oil Elimination Seems Good (Theoretically)

Antifungal treatments are effective for seborrheic dermatitis largely because they inhibit malassezia growth in lab settings [5].

Lab Results vs. Real-World Effectiveness

It’s important to remember that lab results don’t always translate directly to real-world effectiveness. Recent studies suggest that topical antifungals may not significantly reduce malassezia numbers on the skin [].

The logic follows: if malassezia needs lipids to grow, removing lipids from the skin surface should starve the yeast, reduce its population, and clear up symptoms.

This sounds reasonable. If it were true, then drastically reducing sebum production with drugs like isotretinoin (Accutane/Roaccutane) should resolve seborrheic dermatitis.

However, this isn’t the case. In some instances, isotretinoin has even been linked to seborrheic dermatitis-like eruptions [7]. Adding to the complexity, as far back as 1983, researchers stated that “Seborrhoea (excessive sebum production) is not a feature of seborrhoeic dermatitis” [8].

The Problem with Oil Elimination: Damaging Malassezia’s Lipid Layer

The oil-elimination theory overlooks crucial aspects that undermine its effectiveness.

Consider these facts:

- Sebum protects certain skin areas.

- Seborrheic dermatitis affects these sebum-rich zones.

- Sebum is roughly 58% triglycerides and fatty acids [9].

This means malassezia’s basic lipid needs are likely always met on skin prone to seborrheic dermatitis. Completely starving malassezia of oils isn’t practical or aligned with healthy skin function.

What happens if we try to starve them?

Researchers at the University of Leeds investigated this, uncovering interesting findings [10]:

- Malassezia uses fatty acids to create a protective lipid outer layer.

- Yeasts lacking this layer trigger a strong inflammatory response in skin cells.

- An intact lipid layer reduces this inflammatory response.

Furthermore, Korean researchers studied the impact of detergents (like shampoos, soaps, and cleansers) on this lipid layer [11]. They discovered that:

- Common detergents can strip the lipid layer from malassezia yeasts.

- Lipid-depleted yeasts showed a greater ability to induce inflammation.

- Overusing harsh detergents might worsen malassezia-related skin conditions.

Collectively, these studies suggest that aggressively reducing skin lipids can backfire. Instead of eliminating malassezia, we might inadvertently make them more irritating to the skin.

Smarter Strategies for Seborrheic Dermatitis Management

If starving malassezia of lipids is not the answer, what are more effective approaches?

1. Maintain a Low Skin pH

Healthy skin has a slightly acidic pH of around 5. When skin pH rises above this, malassezia releases significantly more irritants [12, 13].

Many soaps and shampoos dramatically increase skin pH, often into the 6-10 range [14]. Combined with their lipid-stripping effects, this can create a problematic cycle.

Choosing pH-balanced and gentle cleansers is a beneficial step. Some dietary adjustments, like increasing Vitamin A and reducing monosaturated fats [15], may also support healthy skin pH.

2. Improve Sebum Lipid Composition

The sebum of skin affected by seborrheic dermatitis differs from healthy skin, notably having fewer unsaturated fatty acids [16, 17].

Improving sebum quality could promote a healthier balance with malassezia. While direct studies are lacking, a multi-faceted approach may be helpful:

- Diet: Focus on healthy fats and antioxidant-rich foods.

- Lifestyle: Support cardiovascular health.

- Topical Oils: Consider applying specific oils to the skin.

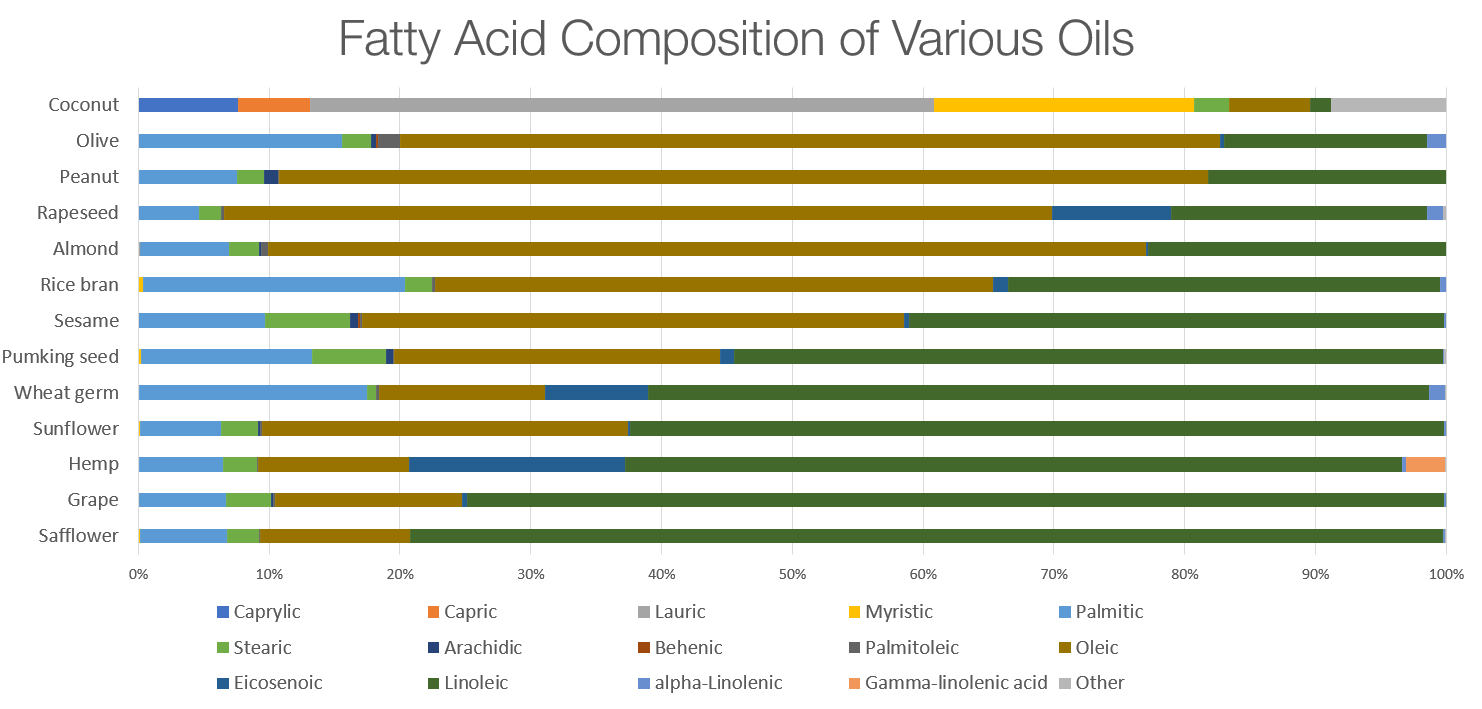

Regarding topical oils, research is limited on which are best for seborrheic dermatitis. However, given the link between oleic acid and irritation, it’s wise to avoid oils high in oleic acid (like olive, almond, and peanut oil).

Here’s a helpful fatty acid breakdown of common oils:

3. Avoid Abrupt Skin Changes

Sudden shifts in skin lipid levels might contribute to the flare-up and remission cycles of seborrheic dermatitis.

Consider this possible sequence:

- Skin lipids encourage malassezia growth.

- Washing with harsh soap abruptly removes lipids.

- Lipid-depleted malassezia become more irritating, triggering inflammation.

- The skin overcompensates by increasing sebum production [18].

- Skin becomes oily, prompting more washing.

This cycle repeats, potentially driving the on-again, off-again nature of seborrheic dermatitis symptoms. Maintaining more consistent sebum levels by avoiding harsh washing may help break this cycle. Next time you reach for a cleanser, consider if you’re disrupting your skin’s natural balance.

In Summary: Rethinking Oils and Seborrheic Dermatitis

Clear-cut answers about seborrheic dermatitis are often elusive. This article aimed to analyze the existing research to determine if fearing oils is truly necessary.

Here are the key takeaways:

- Malassezia furfur can thrive on minimal nutrients: almost any protein and lipid source.

- Sebum-rich skin areas naturally provide ample lipids for malassezia.

- Malassezia’s lipid outer layer is crucial for reducing inflammation.

- Stripping this lipid layer with harsh cleansers can increase malassezia’s inflammatory potential.

- A balanced approach focused on co-existence with malassezia, rather than eradication, is likely more effective.

- Prioritize maintaining a healthy skin pH, improving sebum quality, and using gentle cleansers.

Hopefully, this article provides useful insights to help you manage your seborrheic dermatitis symptoms.

If you have experiences using specific oils for seborrheic dermatitis, please share in the comments below! Questions, suggestions, and concerns are also welcome.

Thank you for reading.

Could you elaborate a bit on how cardio vascular health would effect lipid composition of our sebum ?

Reply Permalink