- Your skin is a multi-layered organ, each layer with a vital role in overall skin health.

- The epidermis, the outermost layer, acts as a protective barrier against the external environment.

- Sweat and sebaceous glands within the epidermis secrete essential substances like sweat and sebum for protection and regulation.

- The acid mantle, a thin surface layer, is crucial for preventing harmful bacteria from thriving.

- Understanding skin structure is key to maintaining healthy, resilient skin.

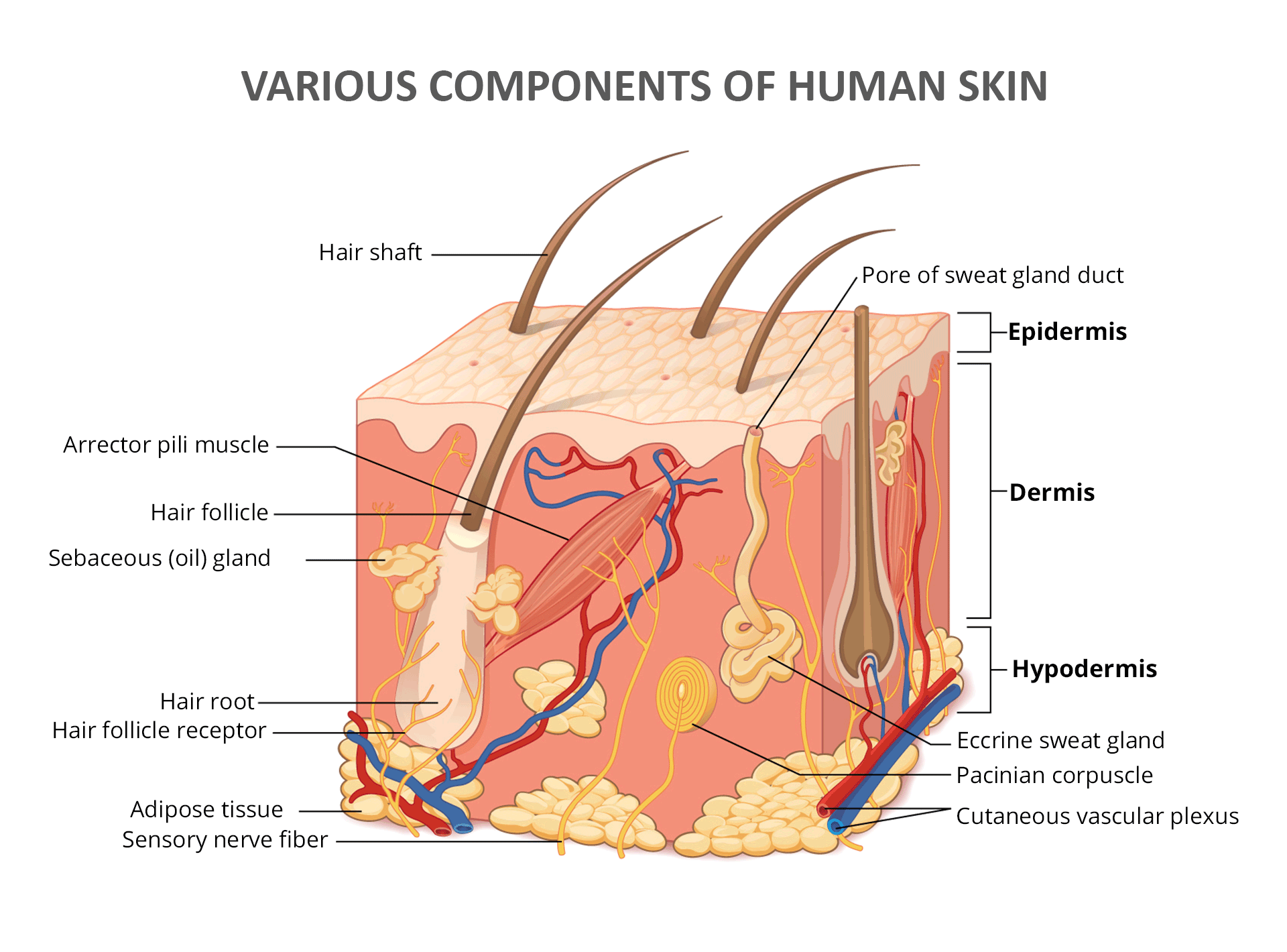

The skin is far more than just a surface; it’s a complex organ composed of distinct layers, each performing specialized functions crucial to your overall health. When one layer encounters issues, it can trigger a cascade effect, disrupting the skin’s overall balance. Let’s delve into the fascinating structure of this vital organ.

The Epidermis: Your Skin’s Protective Shield

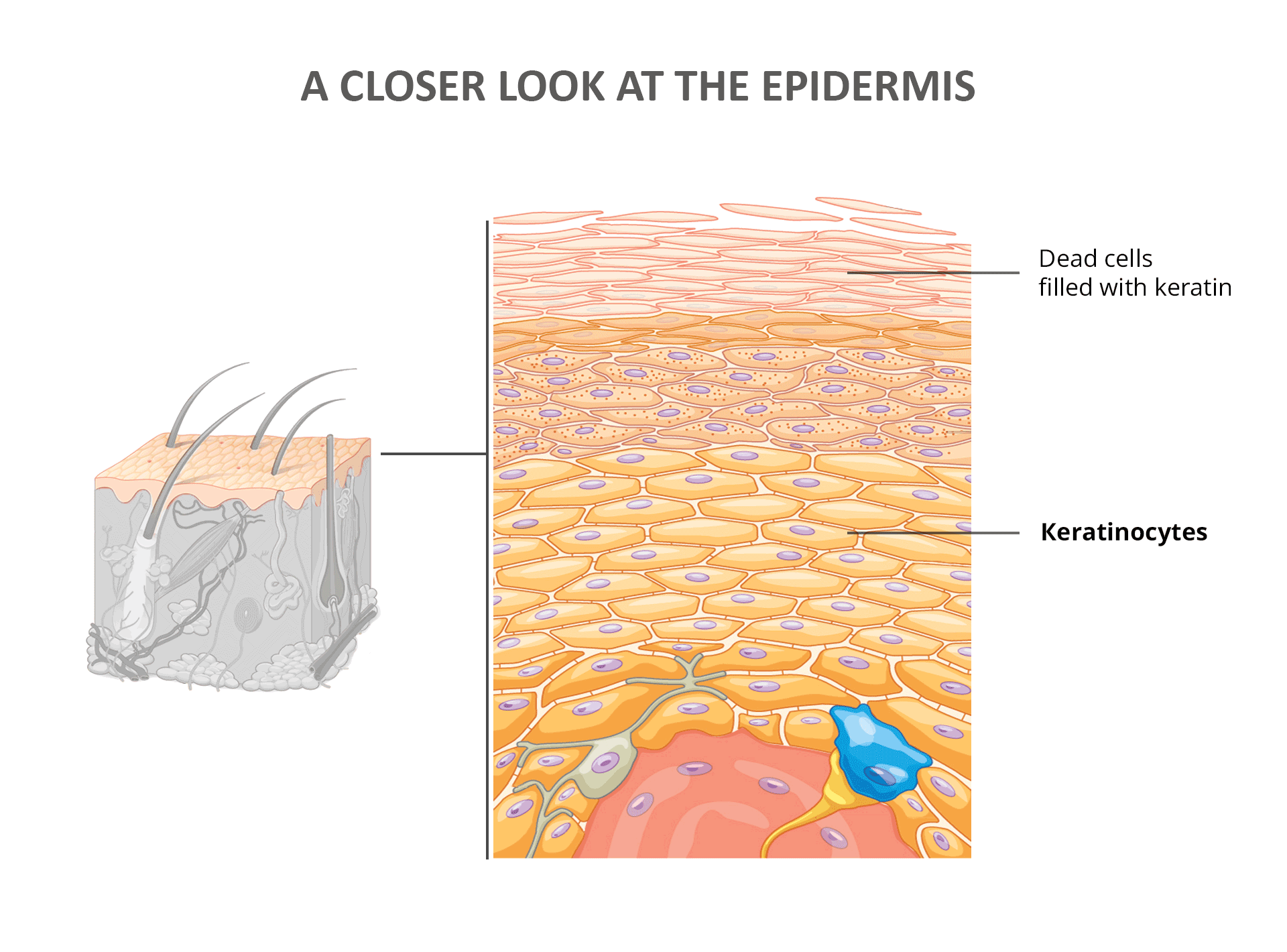

Think of the epidermis, the outermost layer of your skin, as a resilient wall built from “bricks and mortar.” Here, the “bricks” are specialized skin cells called keratinocytes, and the “mortar” is collagen, a structural protein. Unlike a static brick wall, the epidermis is dynamic. Keratinocytes are born deep within this layer, gradually migrate to the surface, and eventually die and shed off, constantly renewing your skin.

This continuous epidermal turnover is a remarkable process, typically taking around 48 days in healthy individuals [1]. For this renewal to function optimally, your body needs to produce healthy collagen and keratinocytes consistently.

However, in certain skin conditions like seborrheic dermatitis [2] and psoriasis, this turnover process accelerates dramatically. This rapid turnover can overwhelm the skin’s ability to produce healthy cells, leading to immature cells reaching the surface prematurely. Given that skin is the body’s largest organ, such imbalances can have systemic effects.

Rapid Epidermal Turnover in Psoriasis

Studies indicate that in psoriatic skin, epidermal turnover can be as fast as 6-8 days, approximately six times quicker than in healthy skin [3].

To appreciate the scale of activity, consider that adult skin covers about 1.5-2 square meters and accounts for roughly 16% of total body weight. Furthermore, each square centimeter teems with life: around 6 million cells, 100 sweat glands, 15 sebum glands, and 400 cm of nerve fibers, not to mention the diverse communities of microorganisms residing on your skin.

Eccrine and Apocrine Sweat Glands: Regulating and Scenting

The epidermis houses two types of sweat glands: eccrine and apocrine, each with distinct roles.

Eccrine sweat glands are distributed extensively across your skin. They are key players in thermoregulation, secreting sweat composed mainly of water, salt, and electrolytes to cool you down. This sweat isn’t just water; it’s carefully formulated with an optimal acidity and antimicrobial peptides like cathelicidin and β-defensins to protect against pathogens.

Research has linked various skin conditions to deficiencies or reductions in these antimicrobial peptides or imbalances in sweat composition [4, 5].

Apocrine sweat glands, in contrast, are more localized, primarily found in areas like the armpits, genitals, and anus. Though present from birth, they become active during puberty. Apocrine glands secrete a richer, oilier fluid containing proteins, lipids, and steroids into hair follicles. Body odor arises when bacteria on the skin consume this secretion.

Sebaceous Glands: Nourishing and Protecting Hair and Skin

Sebaceous glands are intimately linked to hair follicles, forming the pilosebaceous unit – the gland and its associated follicle. These glands produce sebum, a lipid-rich substance vital for lubricating both hair and skin.

Sebum’s complex composition includes triglycerides, wax esters, squalene, cholesterol, antimicrobial peptides, and antimicrobial histones. Its oily nature makes it a prime target for oil-loving bacteria, such as Propionibacterium acnes, and Malassezia yeasts. To combat these opportunistic microbes, sebum relies on the breakdown of triglycerides into antimicrobial free fatty acids and the presence of antimicrobial peptides and histones.

Dysfunction in sebum’s protective capabilities has long been implicated in various skin problems [6, 7, 8]. Since sebum is released into hair follicles, it can unfortunately create pathways for bacteria to penetrate deeper, bypassing the acid mantle’s surface protection.

The Acid Mantle: Your First Line of Defense

Above the epidermis lies the acid mantle, a delicate, protective film on the skin’s surface. This layer is a mixture of lipids, amino acids, sebum, sweat, hormones, lactic acid, and diverse microorganisms.

The acid mantle is your skin’s primary defense barrier. Its slightly acidic pH inhibits the proliferation of harmful bacteria, preventing them from causing infections. A healthy acid mantle reduces the burden on the epidermis and minimizes the likelihood of inflammation, contributing significantly to overall skin health.

Key Takeaways: Understanding Your Skin’s Structure

In summary, this exploration of skin structure highlights these essential points:

- Healthy skin relies on the proper function of its multiple layers; each plays a critical role.

- The epidermis, the outermost layer, is most vulnerable due to its direct exposure to the external environment.

- Keratinocytes, the main cells of the epidermis, originate deep within and migrate to the surface in a continuous renewal process.

- Certain skin conditions, like seborrheic dermatitis and psoriasis, are characterized by a significantly accelerated epidermal turnover rate.

- Sweat and sebum, secreted by glands within the epidermis, are crucial for maintaining skin health and defense.

- Sweat’s composition, including antimicrobial peptides and controlled pH, is vital for skin protection.

- Sebum is a complex mixture of lipids and antimicrobial components that defends against harmful microbes.

- Imbalances or deficiencies in sweat or sebum components can impair skin barrier function, increasing infection risk and skin disease.

No Comments

Be the first to start a conversation